By Lynn Burnett

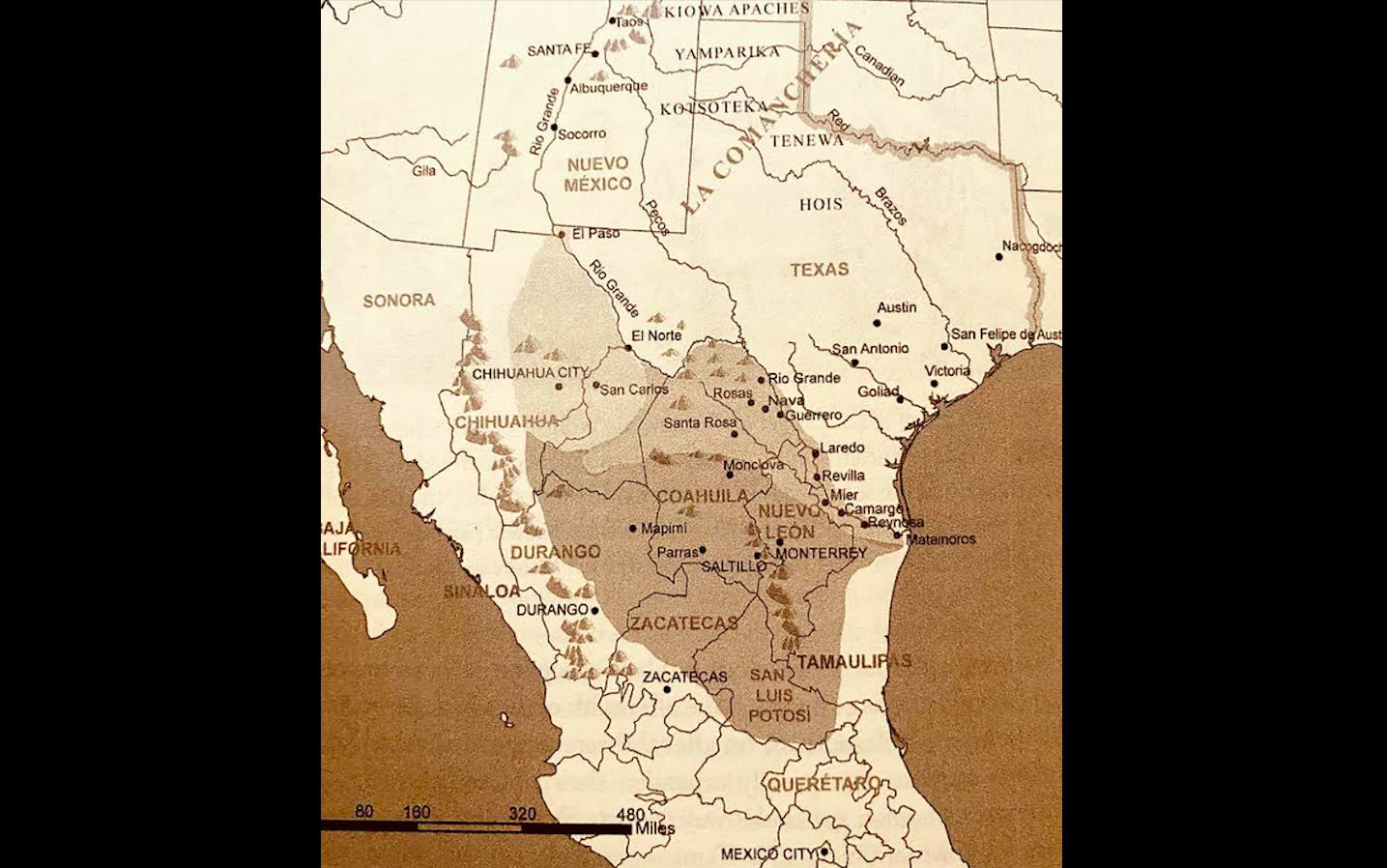

Image: map showing the extent of Comanche raiding into Mexico during the 1830s and 1840s, from Brian Delay’s “War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War.” The following article is primarily based on Delay’s work, as well as Pekka Hämäläinen’s “The Comanche Empire.”

Download the PDF. Support this project.

When the United States invaded Mexico in 1846, the soldiers who marched through what are today Mexico’s northern states encountered desolation. The U.S. Army marched down abandoned roads, past burned-out villages and through deserted ghost towns littered with corpses rotting in the sun. In the words of historian Pekka Hämäläinen, “It was as if northern Mexico had already been vanquished when the U.S. invasion got underway.”

And indeed, it had. The destruction of northern Mexico was the work of the indigenous masters of much of the Southwest: the Comanche. The Comanche had not only prevented the Spanish Empire from pushing further into what would become the United States… they had turned the Spanish colonies of New Mexico and Texas into virtual colonies of their own. Shortly after Mexico liberated itself from Spain, Comanche war bands pushed deep into the interior of the newly independent, but war-weakened country. They forged war trails a thousand miles long that pushed through Mexico’s deserts, mountains and jungles. Comanche warriors raided cities within a mere three-day ride of Mexico City itself. Because of the Comanche, the U.S. Army found the road to Mexico’s capital essentially wide open.

Why, and how, did the Comanche unleash such devastation in Mexico… and by doing so unintentionally lay foundations for American conquest? The story begins a century and half before the U.S.-Mexico War, when the Comanche began to forge an indigenous empire based on dominating the trade in horses and bison hides across the Great Plains, and beyond.

The Emergence of the Comanche

In 1680, the Pueblo Indians living in the Spanish colony of New Mexico revolted. They forced the Spanish out of the region, took control of an enormous number of Spanish horses, and began a lucrative horse trade. The trade in horses moved north from New Mexico, following well-worn indigenous trading routes that moved along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains at the point where the mountain region gradually melted into the Great Plains. Because horses were not found in the Americas before European contact, the indigenous peoples living in the middle of what would later become the United States had not yet encountered the animals. The introduction of horses was a revolutionary moment: tribes who gained access to horses gained immediate and profound advantages in their ability to travel great distances, engage in more extensive trade, hunt, and wage war.

Within a decade, this indigenous horse trade reached the Shoshone peoples living where the Great Plains sweep through modern-day Wyoming and Montana. Bison hunting was at the center of Shoshone life, and horses made the hunt far easier. However, trading in goods that came from Spanish territories also exposed the Shoshone to diseases that were widespread across the massive, interconnected landmasses of Africa, Europe, and Asia… but that had never existed before in the Americas and which Native Americans thus had no immunities to.

As Shoshones fell prey to the kind of contact-induced epidemics that killed millions of Native Americans, a large group splintered off and headed south along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains… following the flow of horses to its source in New Mexico. This group was probably seeking to escape the epidemic, but it also appears they were seeking to establish themselves within the horse trade that had such clear potential to revolutionize indigenous America. As they approached the source of horses in New Mexico, they formed an alliance with the Utes, after which Utah is named. The Utes had long raided horses from the Spanish – who had recently reconquered New Mexico – and they shared their expertise in how to use them in war, hunting, trade, and travel. Over the next generation, the two allied tribes raided so many horses from the Spanish in New Mexico that the settlers no longer had enough horses to mount a defense. The Spanish were soon cursing the new group from the north as “Comanches”… the Ute word for “enemy.”

Mastering the Southern Plains; Dominating the Horse and Bison Trade

Newly rich in horses and knowledge of the Spanish borderlands, in 1720 the Comanches headed east onto the Great Plains of the Southwest, where immense horse herds could be sustained on the seemingly infinite grasslands. Once on the plains, the Comanche herds grew rapidly. Their horses allowed them to hunt bison with great effectiveness, and the Comanche soon realized that if they focused all their energies on hunting bison and expanding their herds, that they could dominate the regional trade in horses, bison hides, and bison meat. Knowing that they could trade these goods for all the food they needed, the Comanche turned away from farming and foraging, in order to focus exclusively on horses and bison.

In their effort to monopolize the horse and bison trade and eliminate trade competition – especially for the food sources they relied on – the Comanches went to war against their main competitor on the southern plains: the Apache. The Apache had thrived on the plains as farmers, but once they were at war those farms became a military liability. Whereas the nomadic Comanche had no farms or villages to attack, the Apache had to defend the places where they were rooted and which they counted on for food and shelter. By sweeping into Apache villages in the dark of night, destroying their food storages, killing their livestock, burning their homes, and quickly disappearing into the night, the Comanche wore down their competitors on the plains. They combined this type of swift, guerilla style attack with massive frontal assaults that focused on killing as many Apache men and enslaving as many women and children as possible. Following a practice that was widespread amongst indigenous peoples in the region, some of these slaves were sold on the thriving New Mexican slave markets, while others were adopted or married into families and eventually became Comanches themselves. By 1740, the Apache had been forced out of the plains regions of modern day New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas and Oklahoma. Some fled further south onto the plains of Spanish Texas, while others moved to the Rio Grande area and the contemporary U.S.-Mexico border region.

After defeating the Apache, the Comanche emerged as the masters of the southern Great Plains… a land soon known as Comancheria. They quickly became the primary suppliers of horses and bison products in the region, and began building a massive trade network through which they were able to extend their reach far beyond their own territory. In the 1740s, when the French settlers of the Louisiana Territory sought horses and bison robes, the Comanches supplied them by using other indigenous groups as intermediaries between the two regions. In return, the Comanches received manufactured French products… including iron axes, metal tipped arrows and lances, and most importantly guns that were superior to anything made by the Spanish. The Comanche then used this superior firepower to raid Spanish-controlled New Mexico for horses, which they then sold to the French, who then gave them more weapons. By 1750, this cycle had created busy commercial routes connecting Comancheria and French Louisiana.

By 1750, the Comanche population had grown to fifteen thousand… and it was rapidly increasing. The main driver of their population boom was an abundant food supply, based on the Comanche’s ability to trade cherished horses and bison robes for plentiful and diverse foods. Their horse herds were probably upwards of thirty thousand, and that was rapidly expanding as well. By this time, Comanches had broken up into dozens of bands consisting of large extended families, so that their horses would have enough space to graze and find water. This rapid population growth, combined with the desire to acquire new markets, created pressures to expand into new territories. The Comanche bands to the south thus pushed into the vast plains of Spanish Texas, where a million wild horses roamed… and just as importantly, where isolated and vulnerable Spanish missions and presidios held abundant supplies of tamed horses ready for the taking. Because training wild horses was a high-skill task requiring weeks of labor, in their efforts to monopolize the region’s horse trade, Comanches sought out vulnerable and abundant supplies of domesticated horses that could immediately be traded. Over the following century, this would lead Comanches to constantly push into new raiding domains.

When the Comanche arrived on the southern plains of Spanish Texas, they encountered their old Apache competitors who they had forced south. Once again, they set themselves to forcing the Apache out of the region. This time, however, the Apaches were allied with the Spanish. The Comanche responded by forming an alliance of their own with the smaller indigenous groups of the region, who felt marginalized by the Apache/Spanish alliance. The Comanche-led alliance – which the Spanish referred to as the Norteños – attacked Spanish missions and presidios with indigenous armies that were up to two thousand warriors strong and armed with French guns. Reinforcement armies sent from Mexico City were defeated by well-armed Comanche warriors, who were by this time some of the best horseback riders on the continent. They were faster than the Spanish, could fight better on horseback than the Spanish, and used guerilla warfare tactics that the Spanish were unable to adjust to. The Comanche forced the Spanish to realize that they were not the strongest power in Texas. In an attempt to appease the Comanche, the Spanish severed their alliance with the Apache, who fled to the region of the current U.S.-Mexico border. Now completely forced out of the plains and alienated from the Spanish, the Apache initiated decades of systematic raids on the Spanish settlements of what is today northern Mexico.

In 1763, however, the Spanish saw their luck turn around… or so they thought. In that year, the French were forced to turn over the Louisiana Territory to Spain after suffering defeats in the Seven Years War. With the French gone, Spain assumed the Comanches would lose their access to guns, gunpowder, and ammunition. They assumed that Comanches would be forced to turn to the Spanish for European manufactured goods, and would be forced to cease their raiding in order to build better trade relations with Spanish territories in order to gain access to those goods. The Spanish further assumed that once the Comanches ceased their raids, that they would be able to strengthen their colonies in New Mexico, Texas, and Spanish Louisiana… thus hemming the Comanche in to the west, south, and east.

The Comanche, however, had other ideas. By this time, they had dominated the entire portion of the Great Plains that was suitable for breeding and raising horses. On the northern plains, the winters were too cold for baby horses to survive, which made breeding impossible. Even on the central plains just north of Comancheria, winter blizzards could sometimes freeze entire herds. The Comanches understood that their northern neighbors required an endless stream of new horses if they wished to survive economically and militarily… and Comanches set out to supply them.

By providing horses to the indigenous peoples of the northern plains who traded with British Canada, the Comanche also secured access to British markets… and British guns. Meanwhile, Spain found itself unable to control the borders of Spanish Louisiana, and French and British smugglers with an interest in weakening Spain pushed into the prime-trading region of the lower Mississippi. The Comanche were thus soon receiving mass amounts of guns from the north as well as the east – one record reveals seventeen horseloads of guns during a single trade deal. Whereas the Spanish had hoped to hem the Comanches in on three sides and cut off their access to guns in 1763, in 1767 a Spanish report warned that Comanches were better armed than Spanish troops.

By the 1770s, the Comanches were selling coveted British and French manufactured goods at trade fairs in New Mexico. Instead of the Comanches turning to the Spanish for manufactured goods, Spanish settlers now turned to the Comanche. However, such trade was not the Comanche’s top priority: that was providing horses to plains Indians, the French, and the British… and the New Mexicans had plenty of horses. Having freed themselves from any dependence on the Spanish markets of New Mexico, Comanches now sought to bend the Spanish colony to their own purposes. Over the course of the 1770s, Comanches launched over one hundred raids into New Mexico, stealing thousands of horses and trading them to the French, British, and the indigenous peoples of the Great Plains.

Comanche raiding parties also sought to systematically weaken the Spanish colony by destroying ranches, farms, food storages, irrigation systems, and slaughtering entire herds of livestock. Their destruction was strategic: by depriving New Mexico of resources, food, and its ability to be productive, the Comanche made New Mexicans dependent on Comanche trade even as Comanches assaulted them. At the same time, they always made sure to leave ranches and farms with just enough resources to replenish their horse herds… so that they could be raided again in the future. Comanches also murdered hundreds of fighting-age New Mexican men during their raids and enslaved New Mexican women and children, some of whom were sold throughout the Comanche’s extensive trade network, and some of whom were used as a source of labor within Comancheria to tend the ever expanding herds of horses and tan the endless bison hides. Entire communities fled in fear. New Mexican settlements vanished from the map. By 1780, only the capital of Santa Fe remained untouched, but the city was overflowing with refugees. The Governor’s Palace had strings of dried Indian ears hanging above its portal to signify Spanish dominance over the region’s indigenous people, but indigenous peoples who had once feared the Spanish now gravitated towards Comanche alliances and markets and spoke more of the Comanche language than Spanish. Spanish officials had planned for the colony of New Mexico to ship surplus goods south into Mexico; instead those goods headed east into Comancheria. New Mexico had become a Spanish colony in name only.

Peace With the Spanish

By this time, the Comanche population had exploded to 40,000… more than the populations of Texas and New Mexico combined. Comancheria encompassed the vast southern plains. Comanches raided New Mexico to the west and Texas to the south at will, removing the resources and enslaving the inhabitants of those lands and channeling them to allies and trading partners to the north and the east. But in the late 1770s, they encountered major obstacles: the American Revolution cut off the supply of guns coming from the French and the British. Droughts forced former allies to migrate into Comancheria, leading to wars along once secure Comanche borders. And then in 1781, right at the height of their powers, a wave of smallpox swept through Comancheria. Half of the Comanche population was dead within two years. Comancheria descended into a realm of horror and sadness. In 1783, the greatly weakened Comanches made the pragmatic decision to open up peace talks with the Spanish. The Spanish, who were unaware at the extent of the epidemic, readily accepted: perhaps their colonies might survive after all.

The Comanche offer of peace came at the perfect time, for the Spanish had just decided to overhaul their relations with Native Americans. With the American revolutionaries victorious, the Spanish immediately foresaw the westward expansion of the United States… and they knew that if Native Americans were hostile to New Spain, that American settlers could ally with them, arm them, and push Spain out of the Americas. If, on the other hand, Spain built positive relations with Native Americans, their alliance could be the best way to prevent westward expansion. And the Comanches would be the most important allies to have when the time came.

The Spanish were serious enough about peace to back off their policies aimed at “civilizing” the Comanches and converting them to Catholicism. They even made efforts to build the new partnership around Comanche cultural norms. In Comanche culture, trade was viewed as a bond that signified mutual support, friendship, and even a sense of extended family. Trade that appeared to be based in greed or coercion had quickly destroyed former attempts at peace: for the Comanches, that included Spanish attempts to sell inferior products, inflate prices, or refuse to trade goods that they possessed in abundance. In their effort to maintain peace with the Comanches, Spanish officials went to great lengths to conform to these norms, and to engage in the generous giving of gifts that Comanches viewed as a sign of friendship. Realizing that Comanches believed that frequent personal and physical contact was critical for strong relations between peoples, Spanish officials journeyed into Comancheria, and welcomed Comanches into the very cities they had recently come close to destroying. There, the officials publicly embraced Comanche leaders for all to see.

The Comanches took the peace equally seriously: Comanches allowed the Spanish onto their plains to hunt for bison. A small group symbolically asked for baptism. And when a group of Comanches broke the peace by raiding into New Mexico, the famed Comanche chief Ecueracapa personally executed the leader of the raid. Ecueracapa later sent his own son to become the son of the New Mexican governor: the governor adopted him as his own and committed to instructing him in the language and ways of the Spanish. Trade flowed freely between Comancheria and Spanish Texas and New Mexico, and Comanches, Texans, and New Mexicans freely visited one another’s lands. It was a remarkable turnaround.

American Expansion; Spanish Collapse; and a Troubled Mexican Independence

American Westward expansion went into full swing in 1803, after President Thomas Jefferson facilitated the American purchase of the Louisiana Territory. Spain had been unable to prevent American settlers from pushing west into Spanish Louisiana, and had sold the territory back to France… which then quickly sold it to the United States. The purchase doubled the size of the young country. Whereas Spain had once hoped that Spanish Louisiana would act as a buffer that would prevent American expansion into the Southwest, they now hoped that a strong Comanche nation, allied with New Spain, would serve as that buffer. Comanches, the Spanish thought, would push back hard against encroaching American settlement.

The first Americans, however, did not come as settlers, but as traders… and the Comanches welcomed that trade. Already in the 1790s, American merchants had been evading Spanish officials to journey into Comancheria for the Comanche’s famous horses and bison hides. By that time, the Comanches had been organizing their society around horses for nearly a century, and had become the recognized masters of horse breeding and training. Just as so many peoples before them, the Americans gravitated towards the Comanche horse trade. Before the Louisiana Purchase had even been made, Americans had purchased thousands of horses from the Comanche. Now that the new American border went right up to the Comanche’s doorstep, trade boomed… especially because Congress, in an effort to break the Comanche away from its alliance with New Spain, sent emissaries to Comancheria to showcase America’s wealth and promise access to it.

The Spanish looked on in dismay as Comanches embraced American trade. By this time, Comanches had also repaired their relationships with the northern plains tribes they had been at war with. Comanche trade was once again orienting itself to the east and the north, leading the Spanish to fear a return to the days of Comanche conquest. And then, things got much worse for the Spanish. In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain, cutting off Spanish resources flowing to its possessions in the Americas. Generous trade with the Comanches became impossible. Then, in 1810, Mexico initiated its War of Independence. New Mexicans – many of whom spoke Comanche, had adopted aspects of Comanche culture, and were more a part of Comancheria than New Spain – embraced Comancheria when the war erupted, and were able to keep the peace with Comanches. Relations between the Comanches and Spanish Texas, however, quickly collapsed. Comanches responded by systematically raiding the Texan colony: using American guns, they removed much of the wealth of Texas and sold it to American merchants. They destroyed what they could not trade. Within the span of a few years, Texas had ceased to be a Spanish colony. It had become the realm of the Comanche.

Thus, when Mexico emerged as an independent nation in 1821, the entire northeastern section of the new country was Comanche-dominated. The Spanish had been unable to control the Comanches, and Mexico was even less able to do so: hundreds of thousands of Mexicans had died during the war for independence, and its economy was shattered. Mexico’s all-important silver mines – one of the great treasures of the Spanish Empire – had been destroyed. Part of Mexico’s postwar plan had been to develop the nation by taxing foreign trade, but high taxes simply led to smuggling and tax evasion. Mexico had expected to secure foreign investment in the wake of the war, but investors looked at Mexico and saw an economically risky environment. Investment didn’t come. In a state of desperation, Mexico took out enormous, high-interest loans from the U.S. and European powers: they quickly defaulted, leaving Mexico’s credit in shambles.

As Mexico’s economic turmoil descended into political chaos, officials were more concerned about internal rebellions closer to Mexico City – or even worse, the very real threat of reconquest by Spain – than they were about the Comanche. Even so, these officials viewed building peace with the Comanches as essential. Like the Spanish, the Mexicans saw American expansion into their territory on the horizon… and they viewed Texas and New Mexico as an important buffer zone between the United States and intrusion into the core of Mexico. In 1821, Mexican officials journeyed into Comancheria, where they spoke before a grand council attended by five thousand Comanche. After three days of deliberation, the council agreed to a truce with the Mexicans. The following year, a delegation of Comanche chiefs journeyed to Mexico City to attend the coronation of Agustín Iturbide as Emperor of Mexico, and to sign a formal peace treaty. The treaty promised generous trade with the Comanches. The Comanches – partly to show their strength to Mexico – promised to raise an army of twenty-seven thousand warriors to fight Spain if it sought to reconquer Mexico.

Political and economic turmoil in Mexico, however, meant that the new nation was unable to live up to the treaty it had signed with the Comanches. As trade with Mexico disintegrated, Comanches returned to raiding with a vengeance. Raiding parties began pushing south of the Rio Grande into present-day northern Mexico… and now, they took not only horses, but slaves. Comanches had been hit by new waves of smallpox in 1799, 1808, and 1816, and they turned to slave raiding to repopulate their dwindling numbers and keep up with the demand for horses and bison hides. Mexican men were usually considered too dangerous to enslave and were typically killed during raids unless they had specialized skills. Mexican boys, however, were put to work taking care of the Comanche’s immense horse herds and tanning the endless flow of bison hides. Mexican women were highly prized as slaves because they could give birth to Comanche children and help to regrow the Comanche population: light-skinned women were especially prized because they, and their children, were more resistant to the smallpox that continuously reduced the Comanche population. These slaves were gradually absorbed into the Comanche population, eventually being adopted into families, intermarrying with Comanches, and ceasing to be slaves… a process that fueled continuous slave raids to replace the slaves who had become Comanches. By the time that the U.S. invaded Mexico, most Comanche families had one or two Mexican slaves.

Trails of Tears; Rebellion in Texas; Slave Raiding in Mexico

While Comanches were turning northern Mexico into a vast slave-raiding domain, trade with the United States boomed. Comanches saw an almost inexhaustible demand in the U.S. for the horses and bison hides they offered, and the more that demand grew, the more of an incentive they had to enslave Mexicans to tend to their horses and tan their bison hides. Comanches also returned to using Texas as a vast horse-raiding territory. These ever-expanding raids led Mexico to make a fateful decision: desperate to populate Texas in order to drive the Comanches out of the region, in 1824 Mexico opened Texas to foreign immigration. Mexico even offered generous land grants and tax exemptions to encourage settlement… and loyalty. They would get one, but not the other.

Mexico had opened up floodgates it could not reverse. Americans began pouring into Texas, but they did not settle throughout the region as Mexico had hoped for. Rather, Americans settled in the east… away from the Comanche raiding territories of the southern plains, and close to the markets of Louisiana and New Orleans that they remained tied to. These Americans brought slaves with them, established cotton plantations, and quickly developed a flourishing cotton industry that was essentially an extension of the American South. Within ten years more than a dozen new urban centers had developed in American-settled eastern Texas. Rather than pushing Comanches out, however, these settlers provided yet another market for Comanches to sell horses to by systematically raiding the Mexican farms, ranches, and villages of western Texas and northern Mexico. Seeing that the plan to entice immigrants to settle Texas was not only a failure but a grave threat, Mexico outlawed slavery in 1829, and banned any further immigration from the United States in 1830. The new laws simply propelled Americans in Texas towards a state of rebellion.

As rebellion simmered in Texas, another momentous event was unfolding: in 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law. The act led to the forced removal of Native Americans into designated “Indian Territory,” west of the Mississippi. The primary targets for removal were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole, whom White Americans had deemed the “Five Civilized Tribes.” These tribes built permanent towns, practiced farming and raising livestock, and traded extensively with White settlers. They formed centralized governments and created written constitutions. Many adopted Christianity and intermarried with Whites. In their efforts to prove that Native Americans could be just as civilized as Whites – and thereby achieve security for their people – the Five Civilized Tribes also took up cotton cultivation, purchased Black slaves, and participated in the cotton trade that was at the center of the global economy.

By so fully assimilating, the Five Civilized Tribes discredited the primary excuse that White Americans used for stripping Native Americans of their land: the notion that Natives were incapable of “developing” the land and making the land “productive.” With this excuse for indigenous dispossession gone, all that was left was violent racism and greed. The Five Civilized Tribes lived on prime cotton-growing land in the Southeast, and the Cherokees had recently-discovered gold on their land. President Jackson agreed with White southerners that they, not indigenous peoples, deserved access to such wealth. The President saw only two solutions: the extermination or forced deportation of Native Americans.

Indian removal led to the infamous Trails of Tears… not one trail, but many, as numerous tribes were rounded up into unsanitary detention centers where they died in large numbers, were forced to march hundreds of miles through harsh winters during which they died of cold and starvation, or died during fierce battles to keep their territory. A full half of the Creeks died on their Trail of Tears, one third of the Cherokees did, and other tribes suffered similar losses. Indian Removal was nothing short of an ethnic cleansing campaign to ensure that the wealth of gold and cotton would remain the domain of Whites only. The Five Civilized Tribes – as well as many others – were pushed right up to the borders of Comancheria on their forced death marches… where they then all had to compete for resources the Comanche had long monopolized. Forced onto arid lands where they could not farm, these tribes pushed into Comancheria to hunt bison. The Comanche waged war on these desperate refugees for infringing on their territory. As the displaced tribes fought for their very survival as a people, the death toll climbed on all sides.

The warfare was unsustainable and disastrous for all. All sides desired peace and sought to find a way forward within their new circumstances. Within a few years, the wars shifted into alliances. The Comanches began hosting massive intertribal gatherings and trade fairs, calling the tribes together for communication and commerce. Many displaced tribes became intermediaries for the vast commercial operations of the Comanches. Like so many before them, the new arrivals turned to the Comanche for the horses they depended on for trade, travel, hunting, and war. They began adopting the Comanche language as the language of trade and intertribal diplomacy, and became deeply influenced by Comanche culture. As displaced tribes adapted to their new circumstances by building strong ties with Comanches, many of their members moved into Comancheria itself, intermarried with the Comanches, and even became Comanches themselves.

The tribes displaced by Indian Removal not only expanded the Comanche population and trade and alliance network, they also provided the Comanches with a massive slave market. The Five Civilized Tribes came from the Deep South, and arrived with 5000 Black slaves who they had brought with them on the Trail of Tears. They now sought slaves to help rebuild their nations in a new land… and to repopulate their decimated tribes, much as the Comanche had done in the wake of numerous smallpox epidemics. Comanches did not have a conception of race – anyone could become a Comanche as long as they adopted Comanche culture; but anyone could become a slave. Comanches had incorporated White renegades and refugees and escaped Black slaves into their tribe as well as Mexicans and numerous indigenous peoples… and, they also enslaved members of these groups. In response to the new market in slavery coming from their recently-made allies, Comanches were soon capturing Black runaway slaves and White settlers to trade to displaced tribes… who often kept the Black slaves, but ransomed back their White captives to White American communities, who were willing to pay high prices. Much more importantly, however, this new market led Comanches to escalate their slave raiding in northern Mexico.

Other factors pushed Comanches to raid deeper into northern Mexico as well: the development of widespread peace with surrounding tribes allowed large numbers of Comanche warriors who had previously focused on protecting Comancheria to instead make long raiding expeditions. Because bravery in battle and the generous distribution of goods taken during raids was an essential part of gaining access to prestige, sex, and marriage for young Comanche men, times of peace led to great eagerness amongst young men to prove themselves on raids. Finally, the massive indigenous trade fairs hosted by the Comanche attracted an increasing number of American merchants, leading Americans to build permanent trading posts along the eastern edges of Comancheria. The Americans had an unquenchable thirst for bison hides, and the trading posts allowed for massive amounts of hides to be stored. Endless streams of merchants came and went from the trading posts, taking bison hides to all corners of the United States. As Comanches supplied the endless flow of hides, more American weapons than ever before flowed into Comancheria. Although the Comanche had traded bison hides for generations, never before had they sought to meet the demands of such a massive market. Comanches once again deepened their slave raiding into northern Mexico: using American guns, they took Mexican slaves to tan the bison hides they sold to the Americans. Comanche profits and power soared. Bison herds started to wear thin.

Meanwhile, full-scale revolution in Texas had broken out. Calls for independence became widespread in Texas in 1835, shortly after General Santa Anna transformed the Mexican presidency into a dictatorship that was willing to use ruthless military force against all who resisted him. White American settlers saw this development as a grave threat to their land holdings and the practice of slavery on which they made their fortunes. Following White American skirmishes with Mexican soldiers, Santa Anna led his forces into Texas to crush the rebellion. After massacring the rebel force at the Alamo – despite their being on the verge of surrender – Santa Anna ordered the few prisoners of war to be hacked to death, and the hundreds of bodies piled up, doused in oil, and burned. Amongst the bodies was famed frontiersman Davy Crockett. The event was widely reported in the U.S. as a brutal episode in an unfolding race war between heroic White Texans and savage Mexicans. It set White American hearts aflame and facilitated anti-Mexican sentiments that in turn laid foundations for war.

Overly confident in his success, Santa Anna divided his forces as he pursued the fleeing rebel army. He then failed to establish a sufficient night watch, leading to his ambush and defeat. White American settlers claimed the independence of Texas, and although Mexico refused to recognize it, there was little they could do. By the time the U.S. invaded Mexico a decade later, there were 100,000 White Americans and 27,000 Black slaves living in Texas. The growing population discouraged Comanche raids within Texas, and gave Comanches an even further incentive to reorient their raids towards Mexico. White Texan officials, understanding that a weakened Mexico was good for an independent Texas, offered Comanches supplies and unrestricted travel through their lands on their way into Mexico.

The Destruction of Northern Mexico; Comanche Collapse

In the decade between Texan independence and the U.S.-Mexico War, Comanches unleashed raiding expeditions more massive than anything before in their history. Historian Brian DeLay documents a minimum of forty-four large raids into Mexico between 1834 and 1847: most had between two to four hundred warriors, but some were eight hundred to a thousand strong. These were highly organized expeditions that moved across multiple Mexican states. They proceeded according to carefully laid plans, moving from one target to the next, hitting ranches, haciendas, mining communities, and towns. Scouts and spies rode ahead to ensure effective attacks. Raiding parties not only took slaves and horses, but – as had long been their practice – murdered fighting-age men, destroyed food supplies, burned homes, and killed any livestock they themselves did not use for food during the course of the raid. To avoid being tracked, raiders scattered in many directions after their attacks, reconvening at planned locations. Each warrior often rode with three or four horses that were specially bred for war: such horses possessed superior speed and endurance and were not for sale, allowing Comanches to keep a military edge. When warriors were pursued they would ride a horse to exhaustion, abandon it, and switch to a fresh horse. Comanches nearly always outran their pursuers. These raiders removed a full million horses from Mexico in the years leading up to the U.S. invasion.

Northern Mexicans, of course, were not passive in the face of Comanche onslaught. They did what they could to develop local militias, and wealthy hacienda owners fortified their properties and hired small private armies. What they needed, however, was assistance from Mexico City in rebuilding the old Spanish presidio system and manning the frontier fortresses with fresh troops. Such support did not come: the federal government decided to use its meager resources to fight rebellions closer to the nation’s capital rather than protect its periphery. Because the farms, ranches, and towns of northern Mexico were isolated and sparsely populated, they were sitting ducks for expert guerrilla warriors like the Comanches. Although Mexican militia did sometimes succeed at ambushing and killing large numbers of Comanche, this only led Comanches to return and visit extreme retaliation. Comanche violence led to a mass exodus of farmers, ranchers, and rural Mexicans away from the countryside and into safer urban areas, leaving vast portions of northern Mexico unpopulated, unproductive, and open to assaults leading deeper into Mexico.

With Mexico City failing to assist its northern states and local militias woefully unable to fight the Comanche, states experimented with other solutions. In the late 1830s, the states of Durango, Sonora, and Chihuahua passed bills offering bounties for Indian scalps. Soon, scalp-hunting wars raged across northern Mexico, with squads of mercenaries typically ambushing Apaches… who had raided across northern Mexico for decades after being pushed out of the plains by the Comanche. Because Apaches lived in the north Mexican region, they were easier targets than the Comanche, who only travelled into Mexico in large raiding parties before departing again to Comancheria. Mercenaries almost never took Comanche scalps. Indeed, Comanches, seeing an opportunity to make a profit by attacking their old Apache enemies, joined the scalping wars and sold many Apache scalps themselves. The states of Chihuahua and Coahuila then decided to offer tribute to the Comanche – offering their goods freely in exchange for a cessation of raids. Paying tribute, however, continued to deprive those states of resources and simply pushed Comanche raiding parties into other states… especially those further south.

By the late 1830s, northern Mexicans were boiling with anger at their government’s inability and unwillingness to protect them. Starting in 1837, a wave of rebellions rippled across Mexico’s northern states: most wanted to withhold their taxes to the Mexican government so they could develop their own military forces and protect against raiding parties. Some rebels talked of secession. Whereas Mexico City had been unwilling to send military reinforcements to help push back the Comanche, they quickly sent the Mexican Army to defeat the uprisings. Mexicans were soon slaughtering each other instead of fighting the Comanche. By 1840, northern Mexico’s fighting forces had been decimated, leaving the region even more open to Comanche assault. It was at this moment, in the early 1840s, that Comanche war parties pushed all the way into states in central Mexico, including southern Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, and Jalisco. Comanche war trails now stretched one thousand miles long… through Mexico’s northern deserts and up into Central Mexico’s high mountains and jungles. Comanches raided cities a mere 135 miles from Mexico City itself.

The states Comanches now pushed into were not only closer to Mexico City, they were wealthier than Mexico’s impoverished north. When they cried out for support, the Mexican government responded as it never had to the poorer northern states. But it was too late. In 1845 the United States offered statehood to Texas, and soon afterwards launched a predatory war on Mexico that was about pure imperial land acquisition. Military and political officials were well aware of the devastation Comanches had unleashed in northern Mexico, and they sought to take advantage of it. When the U.S. Army marched across the Rio Grande, they encountered a Mexican cavalry riding weak, sickly horses… the only ones Comanches had left them. The cavalry simply withdrew, and the Americans proceeded deeper into Mexico without a fight.

To return to the quote from historian Pekka Hämäläinen with which this story began: “When U.S. troops pushed deeper into northern Mexico in the summer and fall of 1846, they entered the shatterbelt of Native American power. The U.S. Army marched south on abandoned roads littered with corpses, moving through a ghost landscape of ruined villages, decaying fields, horseless corrals, and deserted cattle herds . . . It was as if northern Mexico had already been vanquished when the U.S. invasion got underway.” Northern Mexicans felt little loyalty to Mexico City by the time the Americans arrived, and many hoped that the Americans would protect them against the Comanches given that their own country would not. Many cities in northern Mexico put up no fight at all: in fact, Mexican elites invited American military officials to dine with them, and residents sold the U.S. Army supplies and worked for them as guides. American violence soon changed this initial reception, but during the war there were important battles that clearly would have been won if Mexican forces had been just a little stronger. Northerners blamed Mexico’s defeat on the failure of Mexico City to protect the nation’s frontiers from Comanche onslaught.

First in Texas, and then in Mexico, Americans arrived – in the words of Hämäläinen – “to seize territories that had already been subjugated and weakened by Comanches.” The “stunning success of American imperialism in the Southwest can be understood only if placed in the context of the indigenous imperialism that preceded it.” The Comanche had unintentionally facilitated American Westward expansion and conquest, but it was not westward expansion that conquered the Comanche. During the same year that Texas joined the United States, a two-decade long drought hit Comancheria. Springs and creeks that were essential for life dried up. The luscious grasses that supported immense horse and bison herds turned to a crisp. Bison herds that had already been overhunted by Comanches and their indigenous allies for American markets collapsed into starvation; those bison that didn’t die migrated to the northern plains where there was more moisture. Comanche horses also starved, and Comanches began eating their herds to survive. Comanches had endured many short droughts, but nothing like this. In an astoundingly short time, Comanches lost their monopoly over the horse trade that had sustained their power for more than a century They lost their ability to provide bison furs to the vast American market. The bustling American trading posts on the borders of Comancheria closed down and moved elsewhere. Trade with indigenous peoples to the north dried up. Famine ravaged the Comanches during the 1850s. By the time the next wave of smallpox hit them in 1862, Comanches had already lost half their population. American westward expansion halted during the Civil War years. By the time it began again in the late 1860s, there were only 5000 Comanche survivors, against whom the U.S. waged total war.

Did you enjoy this story? If you’d like to receive updates on the wealth of racial justice resources created by Cross Cultural Solidarity, become a supporter today!