By Lynn Burnett

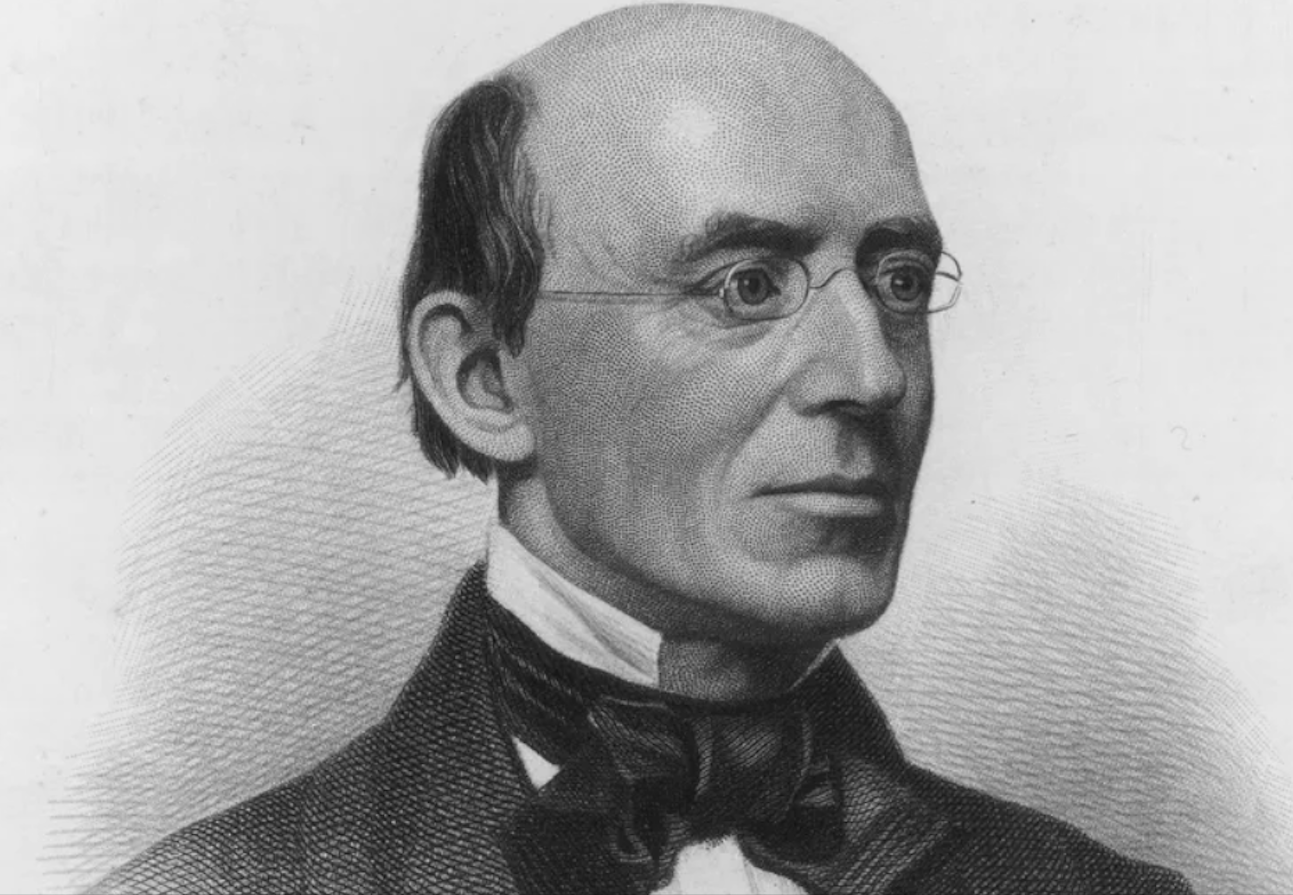

Born in 1805, William Lloyd Garrison founded the weekly abolitionist newspaper “The Liberator” in 1831. The paper was an uncompromising assault on slavery, calling not for its gradual end, but for complete and immediate abolition with no compensation to slave owners. Garrison opened the founding issue with these words: “I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen;—but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present.”

Garrison viewed the press as an essential tool for political change. The Liberator published Black abolitionist voices, first-hand accounts of slavery, and as such quickly gained traction in free Black communities throughout the North. Soon it spread to a White readership in the thousands, and helped to strengthen a network of committed abolitionists. Garrison and other leading abolitionists built on this momentum by founding the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. The organization “drew violent reactions from slave interests in both the Southern and Northern states, with mobs breaking up anti-slavery meetings, assaulting lecturers, ransacking anti-slavery offices, burning postal sacks of anti-slavery pamphlets, and destroying anti-slavery presses. Healthy bounties were offered in Southern states for the capture of Garrison, ‘dead or alive.’” Despite such harassment, by 1838 the Anti-Slavery Society had 1,350 chapters, and boasted 250,000 members.

Garrison also used The Liberator to call for women’s rights, and was an early advocate of women’s right to vote. He urged women to engage in mass petitioning against slavery, welcomed their contributions to The Liberator, and invited them to become prominent members of the American Anti-Slavery Society. When the London-based World Anti-Slavery Convention refused to seat the female delegates sent by the U.S., Garrison gave up his seat and sat with the women in the spectator’s gallery.

Following the abolition of slavery in 1865, William Lloyd Garrison closed The Liberator, resigned from the American Antislavery Society, and called for the formation of new organizations to push for civil rights. The Antislavery Society remained active for five more years, when the 15th Amendment granted Black Americans the right to vote. When Garrison passed away in 1879, his friend Frederick Douglas delivered his eulogy: “It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result . . . He was unusually modest and retiring in his disposition; but his zeal was like fire, and his courage like steel, and during all his fifty years of service, in sunshine and storm, no doubt or fear as to the final result ever shook his manly breast or caused him to swerve an inch from the right line of principle.”

Additional Resources

Books

Henry Mayer: All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery.

Primary Sources

Frederick Douglas: Speech on the Death of William Lloyd Garrison.

Selections from The Liberator.

Harriet Beecher Stowe: letter to William Garrison.

Articles

PBS entry.

Wikipedia entry.