By Lynn Burnett

William Lewis Moore was a Baltimore-based postal worker, who organized with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) during the civil rights movement. In addition to participating in many protests with CORE, the former Marine also advocated for the rights of people experiencing trauma and mental health issues. William also undertook three one-man marches, in which he marched to three different capitals to hand-deliver letters urging government leaders to end Jim Crow.

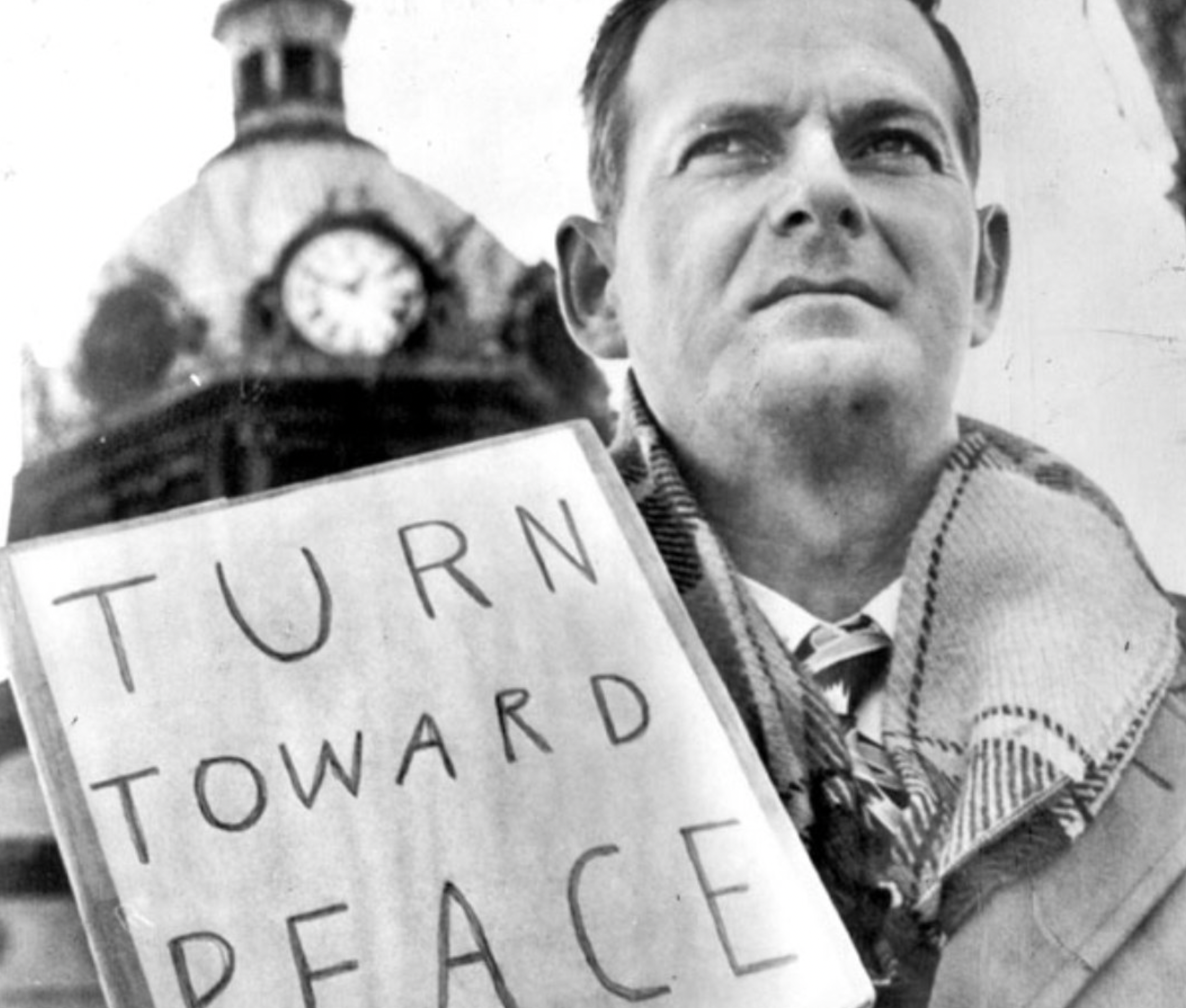

William’s first solitary march was a 30-mile walk from Baltimore to Annapolis, during which he wore a large sign around his neck that read “End Segregation in Maryland” on one side, and “Equal Rights for All Men” on the other. His second march was to Washington D.C. In a letter he hoped would be delivered to President Kennedy, William notified the President that he would be marching to the capital of Mississippi next.

In April of 1963, this mailman-for-racial-justice began a 375-mile march from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Jackson Mississippi. He contacted journalists to let them know about his effort: he believed it would make a good story, and hoped that media attention might spread a message of racial justice to other White folks. William believed that there were plenty of “good” White folks in the South, and that they just needed to be reached.

As William marched through Tennessee, he wore a sign that read “Eat at Joe’s, Both Black and White” on one side, and “Equal Rights for All (Mississippi of Bust)” on the other. He pushed a mailcart containing an extra pair of clothes and a blanket – during the trek William camped on the side of the road. The mailman posted an image of Jesus on the front of his mailcart, with the words: “Wanted – agitator, carpenter by trade, revolutionary, consorter with criminals and prostitutes.”

William Moore’s mailcart was also loaded with copies of the letter that he intended to put directly into the hands of Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett. The letter read: “The White man cannot be truly free himself until all men have their rights. Each is dependent upon the other. Do not go down in infamy as one who fought the democracy for all which you have not the power to prevent. Be gracious. Give more than is immediately demanded of you.” During his solitary walk, William passed copies of the letter to everyone he could, from farmers on the side of the road, to the waitress at a diner where he stopped for breakfast. Some people looked at the letters with confusion, others tore them up, or simply handed them back. Most people were polite, while making it clear that they disagreed with William… and that they hoped he made it to Mississippi safely.

William Moore’s body was found on the side of the road, about 70 miles into his walk, with two bullets in his head. An investigation tracked down the owner of the gun: a Klan member named Floyd Simpson, who was known to have confronted William earlier that day. Witnesses had also seen a car that matched Floyd’s near where William Moore’s body had been found. Southern courts, however, were uninterested in pursuing the murderer of a civil rights worker. No one was ever charged.

In an effort to show that the movement would not allow violence to overcome nonviolent direct action, members of CORE and SNCC quickly mobilized a small group of marchers to finish William Moore’s Freedom March. When they requested that the Justice Department offer them protection, the Department refused. The group was led by Dianne Nash, who was a veteran of the sit-ins and Freedom Rides. The small group started from the spot where William Moore had been murdered, and were quickly arrested.

A second group of ten marchers then began their march from William Moore’s starting point in Chattanooga. Amongst them were SNCC executive secretary James Forman, and White SNCC organizers Bob Zellner and Sam Shirah. During the march, they were pelted with rocks, bottles, and firecrackers, injuring a number of the marchers. (In his autobiography, Bob Zellner almost shrugs this off: “no snipers… no serious injuries.”) As they approached the Alabama state line, they were met by a line of policemen blocking the road… as well as a mob of 1,500 angry White people.

The arch-segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, had been Sam Shirah’s Sunday school teacher, and Sam called him to request peaceful passage through Alabama. Instead, when the marchers refused to disperse and crossed the state line, the police beat them and shocked them with cattle prods. Bob Zellner describes the cattle prods as a form of police torture: “It felt like being hit with lightning . . . It’s one of the worst pains you can imagine.” The prods “burn you and cause you to go into spasms. When the police used the electrical charge on us, the crowd just went into a frenzy.” The CORE newspaper reported the crowd cheering: “Get the goddamn communists! Throw the ni—ers in the river! Kill ‘em!” The group was locked up on death row for 31 days before securing release. During that time they were fed biscuits with shards of glass baked into them. Some of marchers hardly ate for an entire month.

For Sam Shirah, the murder of William Moore and the police torturing of the marchers marked an important turning point. Sam was committed to mobilizing White support for the civil rights movement, and was concerned that if the dominant images of White people in the movement were of them being beaten or murdered, that getting involved in the movement would feel too daunting for the vast majority of potential White sympathizers. Sam began to reconceptualize the role of the White civil rights organizer as being less about putting their bodies on the line for the movement – or even putting themselves in Black Freedom Struggle spaces – and more about going into White communities and developing support. As he later explained: “I think we liberal and radical whites have been wrong in our orientation. We’ve been trying to bring white people into the movement as it now exists. Instead, we should seek to take the Movement into the white communities.”

Sam Shirah would go on to play a pivotal role in two efforts to mobilize White southerners, first in the Southern Student Organizing Committee, and then in SNCC’s White Folks Project. Bob Zellner also went on to engage in like-minded work, especially by founding an organization called GROW that focused on organizing poor White southerners for racial justice during the Black Power era.

Although the murder of William Moore was largely forgotten in the swirl of larger civil rights events, the folk singer Phil Ochs later memorialized the postman in song:

“And they shot him on the Alabama road

Forgot about what the Bible told

They shot him with that letter in his hand

As though he were a dog and not a man

And they shot him on the Alabama road…”

And Pete Seeger sang:

“One day you had a message

You felt you had to shout

It wasn’t an ordinary message

Took you beyond your route

The message dealt with brotherhood

And love and friendship too

It wasn’t a regular message

So they wouldn’t let you through

They stopped you, William Moore, I know

But your message did get through

For they can kill a man for sure

But not his message too.”

Additional Resources

Book: Mary Stanton: Freedom Walk: Mississippi or Bust.

Photos: Bob Adelman Archive: C.O.R.E – Freedom Walk.

Primary Source: William Moore’s letter to Mississippi governor Ross Barnett.

Articles:

Civil Rights Movement Veterans: The Mailman’s March (Murder of William Moore).

Equal Justice Initiative: The Murder of William Moore.

NPR: A Postman’s 1963 Walk For Justice, Cut Short On An Alabama Road.

SPLC bio.

Washington Area Spark: Postman William Moore’s last delivery: 1963.

Wikipedia bio.

Zinn Education Project: April 23, 1963: White Civil Rights Activist Murdered on Racial Justice Walk in Alabama.