By Lynn Burnett

During the civil rights era, Anne Braden worked for the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF), which was dedicated to organizing White southerners for racial and economic justice. However, despite Anne being one of the most famous White antiracists in U.S. history, the story of the organization she worked for is little known…

Launched in 1942, SCEF was originally the educational branch of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. SCHW was one of the “popular front” organizations during the 30s and 40s that brought liberals together with socialists and communists in order to fight the threat of fascism. After World War II, popular front coalitions began to crumble, and under the pressures of McCarthyism disintegrated almost entirely. As a successful popular front organization advocating anti-lynching legislation, widespread voter registration, labor unions, equal schooling, and other civil and economic rights issues throughout the South, the SCHW came under special attack… although it was largely undermined not by segregationists, but by anticommunist liberalism from within. Even after the SCHW folded in 1948, however, its educational branch SCEF was able to hold on, and branch out into its own organization.

One of SCEF’s major goals was to meticulously document racial inequity in all its forms… and then build support for racial justice by showing how those inequities held back the South as an entire region, and led to inferior schooling, healthcare, and employment for the majority of White southerners, as well as Black. SCEF’s newspaper, the Southern Patriot, communicated these inequities and the struggles against them to members of the old popular front, even after much of that front had crumbled. It also highlighted examples of White antiracism, in the hopes that those examples might inspire other White people.

SCEF polled White university workers, doctors, politicians, and other White Southerners about their racial attitudes. By gathering such information, they discovered which White populations were more open to some level of integration… groups that included White university and medical workers. SCEF leveraged this information by encouraging, for example, leadership in White hospitals to consider accepting Black patients or training Black doctors. SCEF then used its large network to fundraise for any southern institution willing to take on such efforts. In other words, part of SCEF’s work was to discover cracks in the edifice of segregation and widen them; to figure out where anti-segregationist embers lay buried in the White South and stoke them.

The 1954 Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education brought mass hysteria and resistance to the South, leading the full weight of McCarthyist redbaiting to come crashing down on SCEF. For over a decade, the organization was under intense assault, including police raids of its offices and the homes of its leaders. At the same time, the Montgomery bus boycott began in late 1955, and opened the door for SCEF to begin working closely with the civil rights movement. Black freedom struggle leaders such as E.D. Nixon of Montgomery and Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham joined the organization, and Martin Luther King began working closely with the group. It was during this time that Anne and Carl Braden joined SCEF.

Despite living under assault, during the civil rights era SCEF did incredible work. The organization leveraged its network to raise funds for legal aid and bail money for the movement, as well as other necessary funds due to the crippling economic retaliation waged by the White South. SCEF brought doctors in from the North to provide medical aid, which was critical given the refusal of White hospitals to treat Black people (as well as White civil rights workers). After the sit-ins of 1960, SCEF hosted workshops for the sit-in students to help them cultivate fundraising and journalism skills. And Anne Braden, as a brilliant journalist, kept White antiracists around the country informed of events through the Southern Patriot.

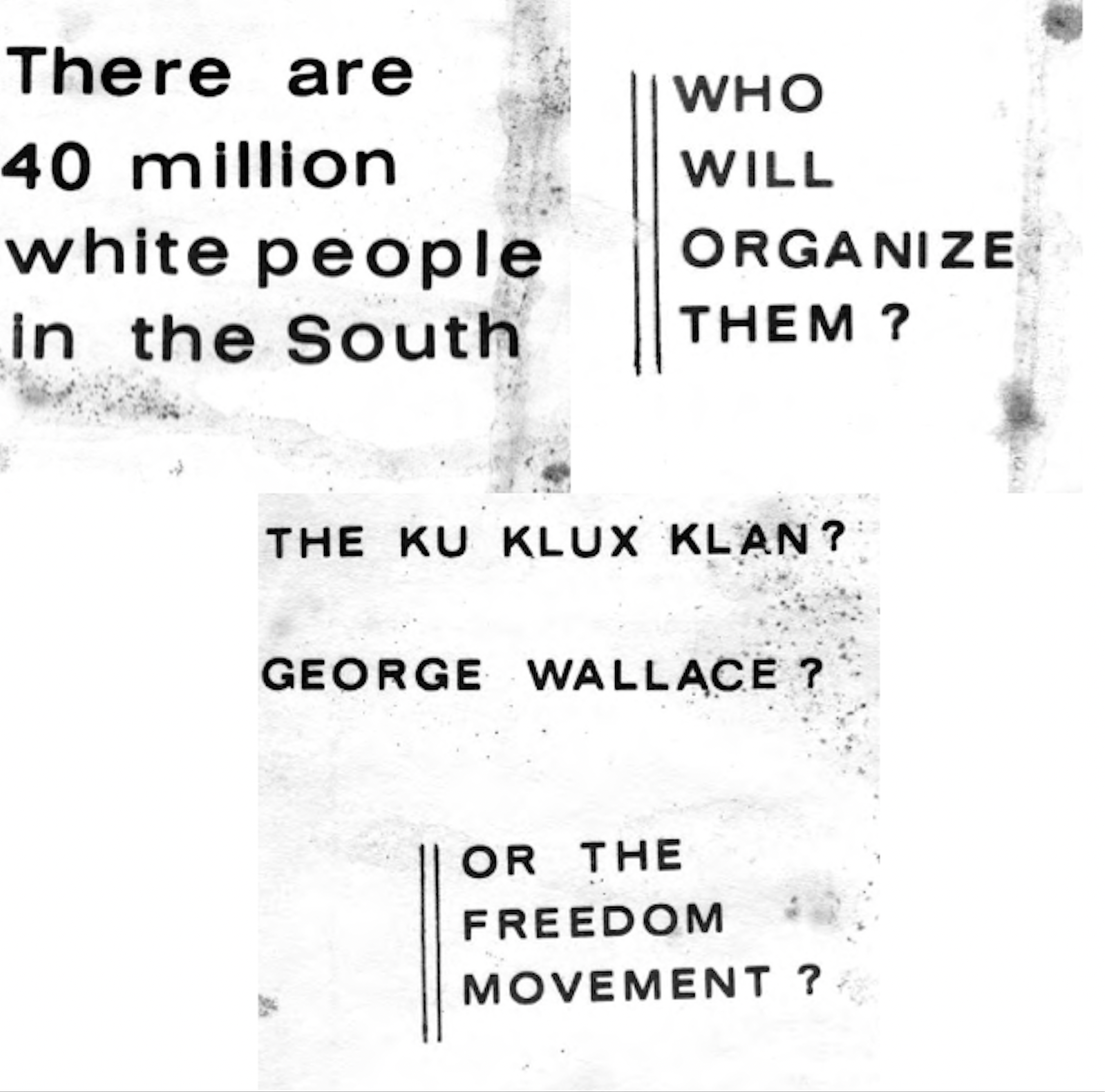

During the Black Power era of the late 1960s, however, SCEF entered a decline. When groups such as SNCC transitioned into all-Black organizations, many White SNCC members poured into SCEF. The Southern Conference Educational Fund fully agreed with the Black Power position that White racial justice activists should focus on organizing White communities, and initiated projects designed to mobilize poor southern Whites and build Black-White working class unity. However, unlike the patient grassroots organizing of the early SNCC years, where SNCC organized rural Black southerners through embedding themselves in the community and engaging in deep listening, many of the new White members of SCEF put their own need to prove how revolutionary they were front and center. This alienated the poor White working class people they were trying to organize. These new White members also tended to view the very people they were trying to organize as the enemy. As Anne Braden put it, “They just didn’t like white people! You can’t organize people if you don’t like them.”

During the Black Power era, SCEF remained committed to being an integrated organization, out of the concern that if it became an all-White organization racism could easily creep in. However, Black Power militants within the group were upset with SCEF’s resources going towards building up White antiracist efforts instead of to Black communities, and tensions escalated into violent standoffs which, combined with dogmatic ideological disputes between the young White self-styled “revolutionaries”, crippled the organization. Anne and Carl Braden, as well as the rest of the staff who had built SCEF, left the organization before it completely imploded. In Anne Braden’s words, “I had spent sixteen years of my life building that organization and saw it destroyed in six months.” It broke her heart. Anne’s biographer Cate Fosl writes, “What three decades of attacks had failed to do was accomplished from within.” It was also true that local police and the FBI leveraged these internal tensions and played a role in turning members of the organization against one another, as they did with racial justice organizations across the nation.

Additional Resources

Books

Catherine Fosl: Subversive Southerner: Anne Braden and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Cold War South.

Irwin Klibaner: Conscience of a Troubled South: The Southern Conference Educational Fund, 1946-1966.

Linda Reed: Simple Decency and Common Sense: The Southern Conference Movement, 1938-1963.

Articles

James Dombrowski: 1958 SCEF memo (primary source).

SNCC Digital Gateway entry.

Irwin Klibaner: The Travail of Southern Radicals: The Southern Conference Educational Fund, 1946-1976.