By Lynn Burnett

Read the prequel. Listen on SoundCloud. Download the PDF and the discussion questions.

In 1904, a Christian priest from England traveled to India. Troubled by the degrading way the English treated the Indians, he began to preach that true Christians would never seek to dominate or control others. Before long, this man joined the struggle to liberate India, causing him to be considered a traitor by his own people. Fighting for the rights of all Indians, he travelled to China, Fiji, and South Africa, where Indians were used as cheap labor and worked under slave-like conditions. In South Africa, he met Gandhi, became one of his closest friends, and stayed by his side as one of his chief advisors for over two decades, until Gandhi, sitting in his prison cell, informed him that the time had come for Indians to know that they could win this struggle on their own.

The man’s name was Charles Freer Andrews. In 1929, Andrews travelled to the United States, where he toured the country’s Black universities lecturing on the nonviolent resistance strategies Mahatma Gandhi was using to force the British out of India. The word that Gandhi used for his style of nonviolent resistance was satyagraha, meaning “soul force.” Gandhi believed that effective nonviolent resistance required people to become strong-souled spiritual warriors, called satyagrahis. Satyagrahis needed to be able to overcome the temptations of anger and violence that would arise when they and their loved ones were beaten, jailed, or even killed. A truly strong souled person could even love their enemies… and out of the force of their integrity, convert would-be enemies to their cause.

This message reminded a deeply religious Black America of the teachings of Jesus, and especially of his teachings from the Sermon on the Mount. In that sermon, Jesus tells his followers that if someone strikes them on their cheek, that instead of striking back they should “turn the other cheek,” offering the other side to be hit as well. This sermon had a powerful effect on the young Gandhi. In Gandhi’s interpretation, Jesus was not asking his followers to engage in weak submission by allowing themselves to be hit. He was asking them to have faith in the potential goodness of the very person hitting them, and by turning the other cheek, to offer them a chance to right their wrongs. Most people would feel a sense of shame at hitting a person who reacted to violence with peace, and many people would be forced to question themselves. Whereas violence only increased the divisions between people, the dedication to nonviolence symbolized by turning the other cheek had the potential to bring people together. For this reason, Gandhi referred to nonviolence as the “discipline of love,” and it was this discipline that Gandhi asked of his own disciples – the satyagrahis fighting for freedom in India.

The sense that Gandhi’s teachings embodied the highest ideals of Christianity allowed the teachings that fueled the Indian freedom struggle to later fuel the Black American freedom struggle. When Martin Luther King later commented that, despite being a Hindu, Gandhi had lived according to Jesus’s teachings better than any other person on the planet, he was simply repeating what Black Americans had been saying for decades. In the 1930s, two decades before King’s statement, Gandhi had entered into discussions with Black American religious leaders. One of these first discussions helped Gandhi recognize the genius of Black American spirituality and its potential for political liberation. It was with the internationally renowned Black scientist, George Washington Carver.

The Mahatma and the Scientist

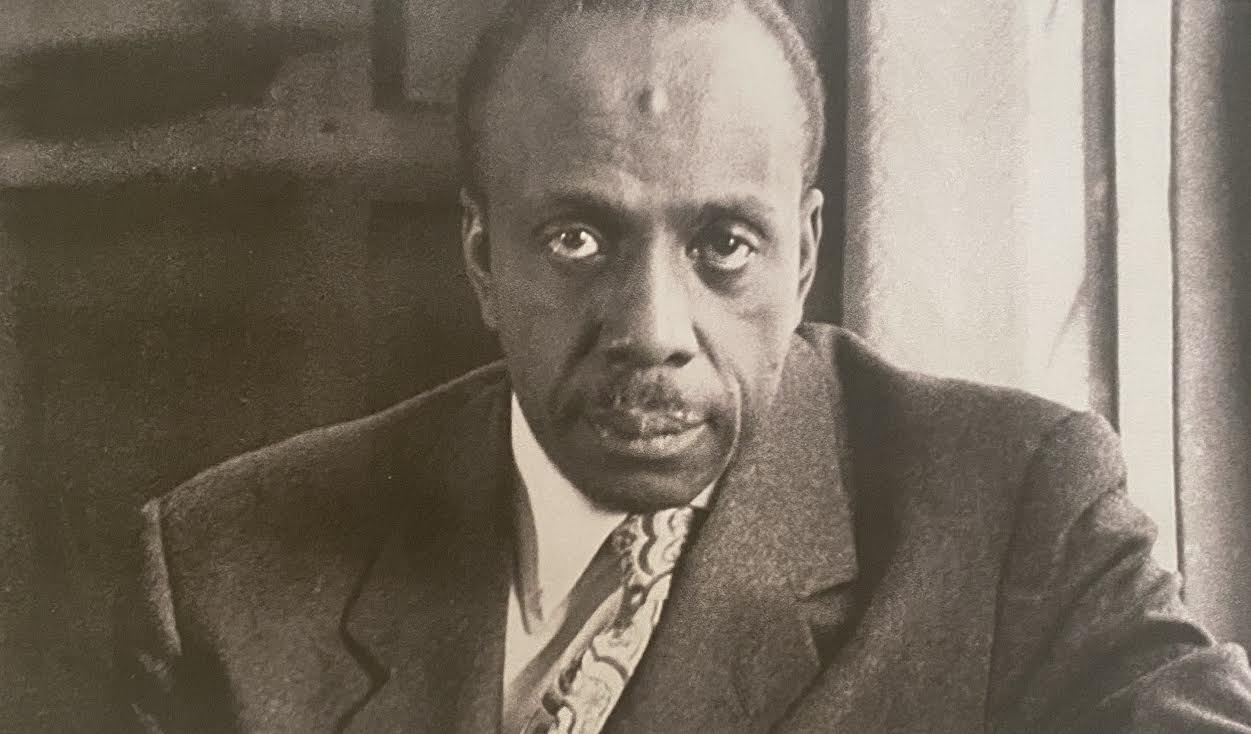

George Washington Carver was a deeply religious man. As a professor at Tuskegee University, he not only engaged in scientific study, but also led a weekly Bible class for over thirty years. Carver credited his strong religious faith for providing him with the insight and inner peace he needed to be a good scientist, and viewed science as a way to understand and honor God’s creation. In his own words, Carver said he prayed to “…the Great Creator silently daily, and often many times per day, to permit me to speak to him through the three great Kingdoms of the world, which he has created… the Animal, Mineral and Vegetable kingdoms; their relations to each other, our relations to them and the Great God who made all of us.”

Carver’s scientific research was dedicated to supporting impoverished Black American farmers, who often struggled to grow food on land that, for generations, had been used for growing cotton plants. Over time, the cotton had stripped the nutrients from the soil, robbing the land of its ability to grow healthy food. Carver discovered that sweet potatoes, soybeans, and peanuts restored the nutrients that the cotton plants had stripped away. He traveled the South, teaching farmers how to restore their impoverished soil. He also taught farmers how to use the resources they had around them in innovative ways – most famously, describing dozens of uses for the peanut, including many uses for the shells alone, from patching roads to insulating houses. If Black families could use their resources well, Carver believed they could invest more in their businesses and their children’s education, and over time, elevate themselves as a community.

While lecturing on satyagraha at Tuskegee in 1929, one of Gandhi’s closest friends, Charles Andrews, befriended Carver. He quickly realized that Carver and Gandhi were similar in important ways. The Mahatma and the scientist were both committed to helping the poorest members of their societies. Gandhi struggled to find teachers willing to travel through India’s villages for little pay to help farmers learn simple strategies for improving their lives, and was very interested in Carver’s discoveries. George Washington Carver created simply written, illustrated pamphlets which, in the words of historian Nico Slate, “addressed how poor farmers could preserve fruit for the winter, produce goods they previously bought, and improve the physical conditions of their homes.” Carver would send these educational pamphlets to Gandhi, who put them to good use in India.

Carver viewed his support of India’s farmers as support for the Indian freedom struggle. More food and of higher quality would translate into a stronger Indian population that was more capable of fighting for their freedom. Carver sent Gandhi a special diet that he hoped would give Gandhi more strength with which to fight for his people. There was also a religious dimension to Carver’s support of Gandhi: both men viewed farming not only as a tool that allowed oppressed communities to be more independent, but also as a sacred connection to the land that brought people closer to God’s miracle. For Gandhi, this meant that agricultural work could potentially help people gain the spiritual strength necessary for nonviolent resistance. Gandhi and Carver also urged the poor to avoid purchasing what they could make for themselves, partly so they could gain economic independence, and partly so that they could develop a faith in their abilities that would make them spiritually stronger.

For Gandhi, spiritual strength was essential for political liberation. Gandhi believed that the strong-souled satyagrahis necessary for waging a nonviolent war against the British also needed to be capable of total self-reliance. Through many hours of discussion with Charles Freer Andrews, George Washington Carver developed his own Christian interpretation of satyagraha, or soul-force. When Andrews returned to India, Gandhi was so impressed by what he heard about Carver that he asked his friend to write an article on him so that Indians could learn from Carver’s example. Gandhi and George Washington Carver would correspond for the remaining decade of Carver’s life.

Gandhi’s Disciple, Mirabehn

In 1935, Black American leaders would finally make direct contact with Gandhi. Howard Thurman, one of the country’s greatest philosophers of religion and a professor at Howard University, led a group of three other Black Americans on a mission to India. The opportunity for the trip arose when a group of Christian students in India invited Thurman to lead a six-month speaking tour on Christianity at Indian universities. Thinking that this might be an opportunity to make direct contact with Gandhi, the philosopher accepted.

Thurman was unsure of how to organize a meeting with Gandhi, but a solution to that problem soon emerged. As the small group prepared for the trip, a European disciple of Gandhi’s arrived in the United States: Madeleine Slade, who Gandhi had renamed Mirabehn. Mirabehn was the daughter of a famous British admiral, and, like Charles Andrews, had embraced Indian liberation. Howard Thurman quickly arranged a meeting with Mirabehn and invited her to lecture at Howard University.

Speaking before a large crowd, she compared Gandhi’s teachings to the teachings of Jesus. She reminded them that Jesus was from the Near East, which, like India, was part of the continent of Asia. When she told the crowd that “the greatest spiritual teachings of the world have all come from the darker races,” she was repeating a theme that many of Gandhi’s disciples had emphasized on visits to the United States. As Sarojini Naidu, the Indian poetess and nonviolent resistance leader had told a gathering of Black Americans a decade earlier, “The African must remember the colored Christ. Preachers did not understand Christ until taught by my Master, Mahatma Gandhi. Jesus, remember, was not a white man, but an Asiatic like me.” By emphasizing that Jesus was “an Asiatic like me,” Indians sought to emphasize a shared spiritual heritage with Black Americans. And by emphasizing that the freedom struggle in India was based on ideas very similar to those of Jesus, Gandhi’s disciples also emphasized that Black Americans could use their own religious tradition for political liberation.

In his autobiography, Thurman wrote that during her lecture, Mirabehn spoke in a calm and gentle tone. And yet, “the intensity of her passion gathered us all into a single embrace, and for one timeless interval we were bound together with all the peoples of the earth.” Howard University’s students were fully prepared to take her message seriously. In 1930, five years before Mirabehn’s visit, two students inspired by Gandhi had refused to move to the back of a segregated bus. The president of the university, Mordecai Johnson, had long urged his students to follow Gandhi’s example. Years later, Mordecai Johnson’s lectures would convince a young man named King – who thought that nonviolence was impractical – to go out and purchase half a dozen books on Gandhi.

Howard Thurman had hoped that through Mirabehn, he and his group would be able to arrange a visit with Gandhi himself. He was not disappointed. Mirabehn, impressed with her experience at Howard University, told him, “You must see Gandhiji while you are there. He will want to visit with you and will invite you to be the guests of the ashram. I’ll talk with him about it upon my return and you will hear from him.” True to her word, Mirabehn returned to India and informed Gandhi of the impressive Black American philosopher who wished to meet him. Gandhi immediately responded, writing Thurman a postcard that read: “Dear friend… I shall be delighted to have you and your three friends whenever you can come before the end of the year.” Gandhi reminded Thurman that his ashram did not have any western comforts such as running water. But the Mahatma assured Thurman that “we will be making up for the deficiency by the natural warmth of our affection.”

The Pilgrimage of Friendship

The trip of the four Black Americans to India was called the “Pilgrimage of Friendship.” When it was announced, India’s colonial rulers attempted to block their voyage, fearing that it would make their rule of India more difficult. The British knew that many Black American intellectuals believed that racial oppression in the United States and European colonization across the world were different parts of the same global problem of White supremacy. If Black Americans could weaken White supremacy in India by supporting Gandhi, that would help weaken the global power of White supremacy, including its hold on the United States. Many Indians felt the same way, viewing Black Americans as important allies who could potentially strike a major blow against White supremacy in one of the strongest nations in the world. As historian Gerald Horne explains, “The far-sighted Thurman sensed earlier than most that engagement with India could be mutually beneficial, striking a blow against white supremacy globally, which would have a decided impact locally.”

A British official scolded the YMCA, which was hosting the trip, saying, “You do not know what you are asking. If an American educated Negro just travelled through the country as a tourist, his presence would create many difficulties for our rule – now you are asking us to let four of them travel all over the country and make speeches!” Despite the protest from the British Empire, the Pilgrimage of Friendship somehow moved forward. However, Thurman’s group was followed everywhere they went by British spies, and it was made clear that they would be removed from India the second they were suspected of contributing to the Indian freedom struggle.

Arriving in India in September of 1935, the group was met with a pleasant surprise: everywhere they went, Indians were well informed of the struggles of Black America. The communication between Black and Indian intellectuals had led many Indians to become interested in the struggle against racial oppression in the United States. But there were also unpleasant surprises: Indians wanted to know why Black Americans had accepted Christianity despite knowing that the religion had been forced on their ancestors by slave masters. One Indian commented that he had read of “one incident of a Christian church service that was dismissed in order that the members may go join a mob, and after the lynching came back to finish the worship of their Christian God.” He told Howard Thurman, “I think that an intelligent young Negro, such as yourself, here in our country on behalf of a Christian enterprise, is a traitor to all of the darker peoples on earth.”

Thurman discovered that being a Christian made it difficult for some Indians to trust him, later writing that “everywhere we went, we were asked, ‘Why are you here, if you are not the tools of the Europeans, the white people?’” Although Gandhi and his disciples had developed a profound respect for Christianity, the majority of Indians seemed to view it as a religion that, in Thurman’s words, “had made its peace with color and race prejudice in the West.” And although many of Gandhi’s disciples believed in a “colored Christ,” other Indians viewed Black Americans as worshipping a white skinned, blue eyed, blond haired savior. This fact caused some Indians to doubt that Black Americans would be useful allies in the global struggle against racial oppression.

Howard Thurman did not take these criticisms lightly. When the Indian man who accused him of being “a traitor to all of the darker peoples on earth” demanded that Thurman explain himself, they entered into a conversation that reportedly lasted for five hours. However, Thurman’s full response would come years later, in the form of a book titled Jesus and the Disinherited. In that book, Thurman argues that Jesus, as a member of a Jewish community conquered by the Roman Empire, had a great deal in common with racially oppressed and colonized people. For Thurman, the religion of Jesus was the perfect response to oppression, which was why Gandhi himself had adopted some of Jesus’s teachings. In response to his time in India, Thurman would also help found the first interracial church in the United States, called the Church For the Fellowship of All Peoples, located in the diverse city of San Francisco and still pastored by one of Thurman’s students today. When Thurman left Fellowship in 1953, the young Martin Luther King considered the position. He chose one in Montgomery, Alabama, instead. It is said that Martin Luther King kept a copy of Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited with him as he travelled, and that he reread it so often that it eventually fell apart.

Meeting the Mahatma

After more than five months in India, and with less than two weeks to stay, Thurman’s group finally had an opportunity to meet Gandhi. The Mahatma was travelling and invited them to stay at his encampment. He normally waited inside of his tent to receive visitors, but when the Thurmans arrived, he came out and welcomed them with greater warmth than Gandhi’s secretary had ever seen before. Gandhi immediately launched into intense questioning about the state of Black America. He wanted to understand all the issues that Black Americans faced and the details of the struggle. The brilliant philosopher had been examined many times before, but Thurman would later write in his autobiography, “Never in my life have I been a part of the that kind of examination: persistent, pragmatic questions about American Negroes.”

Soon, it was Thurman’s turn to ask questions. When he asked if nonviolence required “direct action,” Gandhi may have become concerned that Thurman thought that non-violent resistance did not involve much activity. Gandhi explained that he regretted using the term nonviolence. Instead of helping people understand the actions they needed to take, the term “nonviolence” only described what kind of actions they should not take. However, Gandhi was clearly asking for something much more profound than simply refraining from violence. He had been trying to find a translation for the Hindu practice of ahimsa, which meant to care for all things, through all of ones actions. Hindus considered “actions” to include not only physical actions, but any form of internal movement, including mental and emotional activity. Thus, ahimsa meant developing caring speech, caring feelings, and caring thoughts. Because of this, Gandhi considered translating ahimsa as love, but thought that the word, so heavily associated with romance, would be misleading. And so, he went with nonviolence.

Mahatma Gandhi told Howard Thurman that nonviolence was the “greatest and activist force in the world… Without direct active expression of it, nonviolence to my mind is meaningless.” Thurman pressed Gandhi, in the words of scholar Sudarshan Kapur, “to explain how to train individuals and communities in nonviolent resistance. Gandhi argued that constant practice in nonviolent living was essential.” Individuals and communities that had not developed a nonviolent heart and mind through the way they lived their daily lives would not be capable of nonviolent resistance. It would have been clear to Thurman that the ashrams, or spiritual communities, founded by Gandhi, were meant to support people in developing a nonviolent consciousness. Thurman would also have understood that the church could play this role in the United States.

Before their discussion ended, Howard Thurman’s wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, begged Gandhi to come to America, exclaiming that “We have many a problem that cries for solution, and we need you badly.” Gandhi replied, “I must make good the message here, before I bring it to you.” Gandhi’s connections with men such as George Washington Carver helped him believe that the strong religious faith of Black Americans would give them the strength and inspiration to embrace nonviolent resistance on a massive scale. In Gandhi’s final words to them, he prophesized, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world.”

Two decades later, shortly after the success of the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King’s mentor, Bayard Rustin, reminded King of Gandhi’s prophesy.

The Journey of Benjamin Mays

Towards the end of 1936, Benjamin Mays – a friend of Martin Luther King’s father and the dean of Howard University’s School of Religion – also met with Gandhi. With Mays, Gandhi went into more detail about the intense spiritual activity required by nonviolence, saying that nonviolent resistance “is much more active than violent resistance. It is direct, ceaseless, but three-fourths invisible and only one-fourth visible.” Gandhi added, “Non-violence is the most invisible and the most effective… a violent man’s activity is most visible while it lasts. But it is always transitory.”

More than two decades later, Martin Luther King would explain that although nonviolent resistance was not very physically active, it was intensely spiritually active. King learned this through the message that Gandhi was now teaching Benjamin Mays. Because nonviolence is active mostly in a spiritual sense, it is invisible. The action is spiritual work taking place inside a person – such as the work of overcoming anger or of learning to love – and that action cannot be seen. As Gandhi tells Mays, that “invisible” work is “ceaseless.” It is ceaseless because, as Gandhi told Howard Thurman, it requires the constant practice of nonviolent living.

Benjamin Mays told Gandhi, “I have no doubt in my mind about the superiority of non-violence but the thing that bothers me is its exercise on a large scale, the difficulty of so disciplining the mass mind on the point of love. It is easier to discipline individuals.” He asked Gandhi what he would do if the people in a nonviolent resistance campaign broke down and became violent. Benjamin Mays summarized Gandhi’s response, writing that nonviolent campaigns sometimes needed to be cancelled “if hate develops and love ceases to be the dominant motive for action.” He added that, “In nonviolence, the welfare of the opponent must be taken into consideration.” If the opponent is humiliated, the nonviolent campaign will produce division instead of unity, and create tension that will lead to violence in the future. Leaders had to always be ready to call off campaigns in order to regroup and find ways to maintain the integrity of nonviolent resistance.

Finally, knowing that many Black Americans doubted that nonviolent resistance could work for them since unlike the Indians, they were a small minority, Mays also asked, “How is a minority to act against an overwhelming majority?” Gandhi reminded him that he had begun his own nonviolent resistance struggles in South Africa, where the Indians were a small minority. Gandhi believed that nonviolent resistance had the power to convert people to a cause. If an oppressed minority used nonviolence, the majority of people could be impressed enough to come to their aid.

When Mays – a future teacher of Martin Luther King – returned to the United States, he wrote: “The Negro people have much to learn from the Indians. The Indians have learned what we have not learned. They have learned how to sacrifice for a principle. They have learned how to sacrifice position, prestige, economic security and even life itself for what they consider a righteous and respectable cause.” In another article, he expressed that he was unsure if nonviolent resistance could truly free India. But he did say this: “The fact that Gandhi and his non-violent campaign have given the Indian masses a new conception of courage, no man can honestly deny. To discipline people to face death, to die, to go to jail for the cause without fear and without resorting to violence is an achievement of the first magnitude. And when an oppressed race ceases to be afraid, it is free.”

Bibliography

This story was especially influenced by the profound scholarship of Nico Slate. I am extremely grateful for his feedback and support!

Chabot, Sean. Transnational Roots of the Civil Rights Movement: African American Explorations of the Gandhian Repertoire (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2012.)

Dixie, Quinton H., & Eisenstadt, Peter. Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011).

Horne, Gerald. The End of Empires: African Americans and India (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008).

Kapur, Sudarshan. Raising Up a Prophet: The African American Encounter with Gandhi (Boston: Beacon Press, 1991).

Mays, Benjamin E. Born to Rebel: An Autobiography (London: The University of Georgia Press, 1971).

Slate, Nico. Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Thurman, Howard. Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston: Beacon Press, 1949).

Thurman, Howard. With Head and Heart: The Autobiography of Howard Thurman (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1979).

Additional Resources

From Black Desi Secret History and the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour comes: The Secret History of South Asian and African American Solidarity.

The Church of the Fellowship of All Peoples, founded in San Francisco by Howard Thurman, is still active and led by Dorsey Blake, who was personally appointed by Sue Bailey Thurman.

When Howard Thurman Met Mahatma Gandhi, by Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt.

From Minerva’s Perch: The Thurman Delegation in India.

From “Made By History” at the Washington Post: The overlooked heroes of the civil rights movement: Remembering Howard Thurman and other forgotten activists.

From the Black Agenda Report: The Influence of Gandhian Socialism on Du Bois and King.

Martin Luther King: My Trip to the Land of Gandhi.

Questions

- Thinking About Strategy: How did Gandhi interpret Jesus’s teaching of “turning the other cheek?” Why did Gandhi think this teaching could overcome division, and create unity?

The Mahatma and the Scientist

- Thinking About Science: In what way was George Washington Carver’s scientific research dedicated to supporting impoverished Black farmers?

- Thinking About Strategy: Why did both Gandhi and George Washington Carver consider farming and nutrition to be an important part of fighting for freedom?

Gandhi’s Disciple, Mirabehn

- Thinking About Strategy: When Gandhi’s disciples met with Black Americans, why did they focus on discussing Christianity? Why did they emphasize that Jesus was “Asiatic?”

The Pilgrimage of Friendship

- Thinking About Global Context: Why did Black Americans and the people of India want to support each other? And why did the English want to prevent this?

- Thinking About Strategy: Why did many Indians doubt that Black Americans would be useful allies in the struggle against racial oppression?

- Thinking About Religion: How did Howard Thurman respond to the Indian criticisms of Black American Christians?

Meeting the Mahatma

- Thinking About Public Perception: Why did Gandhi regret using the term “nonviolence” to describe his vision of resistance?

- Thinking About Strategy: According to Gandhi, what did people need to do to effectively train themselves for nonviolent resistance? What role did the ashrams in India have in this training… and what role might the churches in America have?

The Journey of Benjamin Mays

- Philosophical Thinking: According to Gandhi, why was nonviolence mostly “invisible?” Why was it “ceaseless?”

- Thinking About Strategy: Why did Gandhi believe that nonviolent resistance needed to “consider the welfare of the opponent,” and never humiliate the opponent?

- Thinking About Strategy: According to Gandhi, why could a small and oppressed minority successfully use nonviolent resistance against an overwhelming majority?