By Lynn Burnett

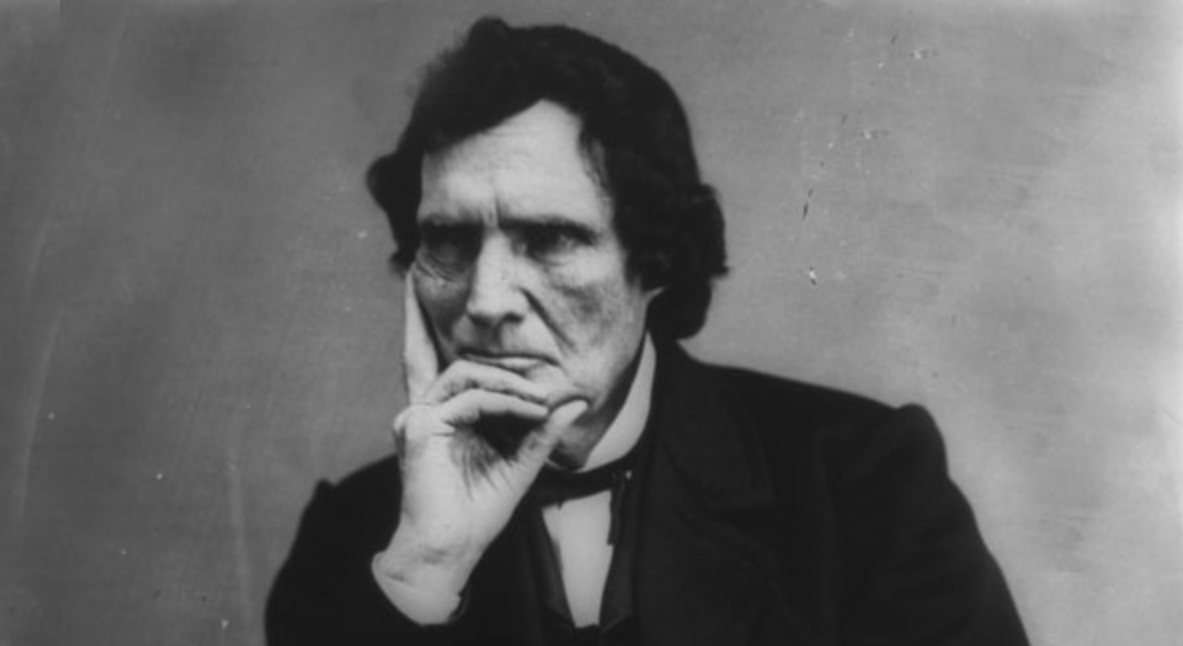

During the Civil War, Radical Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens led the charge for the immediate abolition of slavery, the enlistment of Black soldiers, land redistribution to secure economic stability for freed slaves, and the right to vote. The congressman introduced a bill to abolish slavery shortly after the war began, and was exasperated when Lincoln took another year merely to call for emancipation in the border-states. Thaddeus and his fellow Radical Republicans – called radical because of their call for immediate abolition – held Lincoln’s feet to the fire, leading the president to comment: “Wherever I go and whatever way I turn, they are on my tail.” Even after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, Thaddeus Stevens pushed for more. The Proclamation did not apply to all slaves, and it was a wartime measure that could be reversed when the war ended. It was Thaddeus Stevens who led the charge for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery, which culminated in the passage of the 13th Amendment.

As early as 1862, Thaddeus called for permanent land redistribution as a way to create a solid economic foundation for former slaves, which he (and they) saw as a prerequisite for true freedom. Other measures such as General Sherman’s wartime order allowing slaves to settle on abandoned land did not grant them legal title to the land, and it was quickly stripped from them. Thaddeus Stevens instead proposed confiscating land from the wealthiest two percent of plantation owners, in order to provide forty acres to former slaves. He assured poor and middle-class Whites that their land would remain untouched, and argued that it made sense to redistribute wealthy plantation land because slaves had long worked that land with no compensation. His arguments, however, were deemed too radical even by many of his allies, who saw it as an unconstitutional assault on private property. The failure to provide former slaves with land quickly led to the rise of the neo-slavery systems of sharecropping and convict leasing.

When Thaddeus Stevens passed away in 1868, he had two Black preachers by his bedside, as well as Lydia Hamilton Smith… a Black woman he had lived with for twenty years and who was officially his “housekeeper,” although many suspected the relationship was more than that. For the following century, Thaddeus would live on as the arch-villain in the White southern imagination: Villains in Jim Crow stories and movies were often based on caricatures of the Radical Republican. The same qualities that made him a villain in the White South made him a hero to many Black Americans, who named schools, organizations and awards after him. Frederick Douglass even kept a portrait of Thaddeus Stevens hanging on his wall.

Additional Resources

Book

Bruce Levine: Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Racial Justice.

Articles

Eric Foner: Thaddeus Stevens, Confiscation, and Reconstruction.

Matthew E. Stanley: The Radicalism of Thaddeus Stevens.

James A. Delle: Excavations at the Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith Site, Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Archaeological Evidence for the Underground Railroad.

Wikipedia entry.